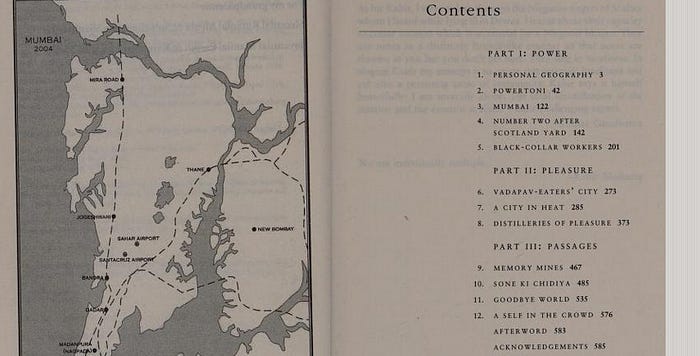

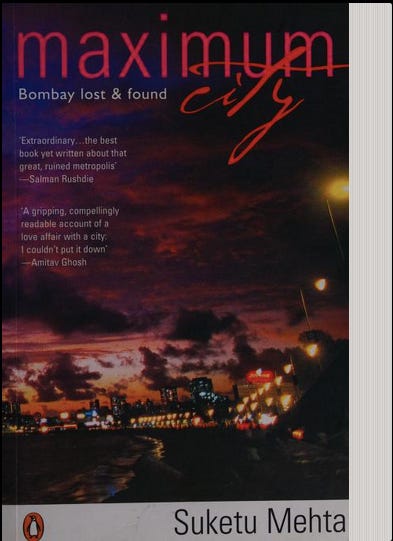

Why Mumbai Is Called The Maximum CityA literary delve & summary of Suketu Mehta’s book Maximum City: Bombay Lost and FoundIt’s 9:00 a.m. on a Saturday morning here in Mumbai city as I write this piece; I’ve just finished my 5km run & the smoke from my last cigarette is slowly fading into the cold thin air, which has a slight nip floating around & it’s the perfect day to write this article about my city: Mumbai. Mumbai is an emotion. It’s the city of dreams for people in India. Thousands flock from villages & cities across the country to Mumbai, for some bit of work, to earn basic wage or to try and sell their services, whether that’s pani puri walas, cab drivers, watchmen & security guards or cleaners, clerks and other kinds of blue-collar workers or businessmen trying to set up shop in the city. To put it into canonical terms in terms of global urban identity, Mumbai can be likened to the New York of India. It’s a city on the shorelines of the Arabian Sea instead of the Atlantic, it’s the financial capital, as it’s home to the BSE or Bombay Stock Exchange, it’s the most populated city in India (of over 23 million people) and the place where the underdog lives their life on a lullaby, keeping themselves riding on that train, just like that Kasabian song goes. It’s the city where the streets echo the charm & industry of hustle, the incandescent glimmer of opportunity & the stench from the gutters and betel paan spit that aligns the nooks and corners of the alleyways. In this brief (or somewhat brief) article, I will break down the book Maximum City: Bombay Lost & Found by author Suketu Mehta, which is a book which I have fond memories of reading when I was living away from Mumbai while studying my undergraduate degree in engineering away from my hometown & the city I was born in and call home. This is why Mumbai is the “Maximum City”… Part I: PowerThis section of the book is all about the “black”. In Mumbai and in India, the term “black” or “black money” is used for untaxed or unaccounted for & stashed cash; hard cash, which almost every household, whether they’re poor, middle class or rich industrialists, have at some point in time kept in cupboards & closets along with gold ornaments & other valuables. It’s income that’s not reported to the government & even real estate deals comprise a portion of “black” in the negotiations. Also, in the event that tax collection agents get a tip and happen to “raid” a rich family’s home. They’re bribed with the “black” money as well. In “Personal Geography,” Mehta writes about his return to the city of his childhood after spending time away in America, marking his homecoming as a writer aiming to write this book. He writes about the stark contrasts of living in Mumbai compared to the US as he places himself inside the city’s moral veil. The city, architecturally speaking, was built on land reclaimed from the sea and nearby tributaries that run through its vast, long and broad landscape. And it’s also called “the island city”. Mumbai is described as both an intimate and brutal city at the same time, like a quantum particle that can exist in two states at once. It’s a place where, to belong, you need to understand the language and mannerisms of the streets & the heartbeat of the city. In the chapter “Powertoni”, a term expanded by Mumbai-slang from just “power”, Mehta dissects and delves into the Mumbai underworld, revealing how organised crime emerges & operates from the shadows, almost echoing the city’s entrepreneurial spirit but with a darker twist. Back in the ’90s, in Mumbai, notorious underworld gangs ran the streets & the black markets. The most famous of the underworld dons was, of course, Dawood Ibrahim, who orchestrated the serial bomb blasts of Zaveri Baazar, an affluent jewellery boulevard in South Mumbai. He was later convicted as he fled to Dubai to seek escape & refuge, as Interpol aimed to track him down. I was only 3 years old in 1993 when the blasts occurred, but my family still tells me of how scary & grim it was, as everybody was scared to venture out of their homes. There were also other dons like Chota Rajan, Chota Shakeel and Haji Mastan, and several others who have been popularised by Bollywood film culture. The mafia in Mumbai back then ran as a parallel administration, responding faster and more efficiently than even the state itself. It was where things were handled or sorted out by gang members with “ghodas” (literally “horses” but slang used for “guns”) in their jackets. One line particularly captures the combination of fear and admiration of Mumbai’s “Powertoni”, where Suketu Mehta writes, “The don is the shadow mayor.” In the chapter “Mumbai,” Mehta metaphorically refers to Mumbai as a living organism whose metabolism runs on migration, ambition, and exhaustion. Mehta dissects how survival in the city itself becomes a form of intelligence & jugaad (“to figure out a way” in Mumbai slang). He romanticises the hustle & struggle and the glory and freedom all in evocative paragraphs. It’s a delve into Mumbai being more of a vibe than merely a city, in today’s common parlance (thanks to Gen Z). “Number Two After Scotland Yard” reveals the crooked venality of the Mumbai streets further by flipping the script from the gangsters to the “gangsters in uniform”, i.e., the corrupt Mumbai police. Mehta writes about how the police are overworked, underpaid, and morally & ethically loose. Law enforcement in Mumbai smoothly operates with the accumulated greasing of every “hawaldar(slang for regular police officer)” policeman’s palm with cash bribes. The cops are crooked & the system bends because the city demands it. However, despite the rampant corruption, which has significantly reduced in today’s times, the Mumbai police did have a redemptive moment when handling & neutralising the Pakistani terrorists who attacked the city in 2008 (an incident also known as 26/11). “Black-Collar Workers” closes the first section of the book by examining white-collar crime, from industrialists to business owners and the Mumbai elite, exposing how corruption is not confined to just the gangs & cops & slums or back alleys, but in every entrepreneurial venture & the local state/city parliament, where scams & black money flow like a smooth cover drive off of 90s and 2000s Mumbai cricket icon (& nearly godlike figure), Sachin Tendulkar’s bat. “Everyone is hustling”, writes Mehta in the chapter fittingly termed “Black collar.” This is the premise of why Mumbai is the Maximum city, because survival, intelligence & jugaad (or finding a way) remain essential no matter what social strata you’re from if you’re living in the city. And the money talks… Part II: PleasureMumbai & Mumbaikars love to indulge. In the chapter “Vadapav-Eaters’ City”, Suketu Mehta explores the varied array of food, taste, indulgences & eating habits of Mumbaikars. Street food in Mumbai is almost a staple, whether that’s vada pav, pani puri, idlis & dosas or rolls, whatever can be eaten quickly & on the move. Food is in a hurry in Mumbai, too. Mehta writes of enormous queues that line up to eat food at famous stalls or cafes with bodies packed against each other like the local trains, all to indulge a bit in the heat, spice, and flavour. Then, in the chapter “A City in Heat”, Mehta asserts the sexual heat that boils up in the city with explicit candour. “No one here need be alone”, he writes. Desire in Mumbai is public and private simultaneously, and yet irrepressible. The city’s murky grasp intensifies longing as soon as dusk settles in. Another line reads, “There is no privacy, only secrecy.” In “Distilleries of Pleasure”, Mehta explores Mumbai’s vivid nightlife, voracious capacity for alcohol indulgence, dance bars, and dance bar girls, building on the previous chapter of how sex is commodified, manufactured, sold, and regulated in the city. Young women’s bodies become pleasure troves for every class of Mumbai inhabitants, & Mehta even interviews a few of the dance bar performers and prostitutes. The dancers are workers too, who are navigating the city’s cruel & insatiable ways with their limited choices, but even they possess sharp awareness, intelligent acumen, & street-smart ways of operating. He also explores a bit about the Bollywood industry, i.e. India’s film industry, which also dwells & is established within the city & is a huge money-making machine. Along with the stock market, think of it like New York’s Wall Street and LA’s Hollywood into one. There’s also the celebration of “Ganesh Chaturthi”, a festival where the city goes into crack cocaine mode as idols of the Hindu God Ganesha are placed everywhere, adorning areas of the city as the citizens dance fervently to music & drums while festive clothes are worn and festive sweets are eaten. Mumbai is a paradox of joy and suffering coexisting together, & Mehta alludes that the indulgences extend to become almost a coping mechanism for its inhabitants for that very fact. Part III: PassagesThe last section of the book is written in a rather introspective & reflective point of view. “Memory Mines” comprises a diverse range of Mehta’s personal memories that often resurface through buildings, neighbourhoods, places and family stories. While in “Sone Ki Chidiya”, Mehta talks about gold and wealth & what it means to different families from different & diverse backgrounds and social status. He further explores how Mumbai hardwires its inhabitants to desire, chase, & nurture wealth because in Mumbai, cash is definitely king. “Some Kind of Chutiyap” is all about Mumbai slang as it captures the city’s humour and despair through language itself. Mumbai slang isn’t fully understood by people from outside the city, but the slang itself becomes a kind of philosophy. The chapter reveals how Mumbai’s linguistics turn the irony of the good & bad sides into brief moments of comedy. “Arre yaar, tu chutiya hai(roughly translating to “Oh friend, you’re a sucker”), almost becomes the rhetoric in every street conversation. The chapter “Goodbye World” is the book’s emotional centrepiece as it nears its end. Mehta interviews and writes accounts of people whose lives are marked by illness and death, and how mortality in the city is not softened by spirituality but rather echoes the ephemeral nature of life, just like every wave of the tides on Marine Drive comes and goes. A very powerful line in the book reads: “The city teaches you how to let go.” The final chapter, “A Self in the Crowd”, closes the book by returning to the question of identity as Mehta tries to comprehend and piece together his own life & those of others who inhabit the city & everyone he’s written about in the book. In Mumbai, the self dissolves into the city. And this is the transformation and humbling that the city offers. Mumbai: The Maximum CityMumbai is a diverse landscape of geography & people that isn’t just like any other city. The reason Suketu Mehta calls it “maximum” is that it’s not just the size and scale of the city that befits the nickname, but it’s through the intensity of living in it. Mehta doesn’t elicit that Mumbai is a paradoxical or enigmatic city because it is chaotic or cruel or both. Of course, it’s a lovely city to visit as a tourist. It’s iconic to say the least. Whether that’s immersing yourself in the architecture & cafes of South Mumbai or walking or sitting on Marine Drive as the Queen’s Necklace of streetlights along the stretch flicker on as day gives way to night. Or whether it’s the other parts of the city, like the nightlife & glitz and glamour of Bandra, Lower Parel or Andheri. Or now, given the sheer scale of the city’s expansion, even visiting the suburbs (which have better architectural planning) or the slums of Dharavi, where the poorest of the poor of the city dwell. But this is a city that requires you to adapt & be street smart and intelligent. You cannot “live” in Mumbai without being a part of it. And for all its black, grey, white and colour, it’s a city unlike any other anywhere in the world. If you’re curious, I’d highly recommend buying & reading the book, or alternatively, you can also read it for free on Archive.org(linked below): https://archive.org/details/maximumcitybomba0000meht/ If you liked this article, you can buy my book Make Your Own Waves, which comprises 45 thought-provoking perspectives on life, which you can buy at the link: https://amzn.eu/d/dZaX8Dr If you’re in India, you can buy it here: https://amzn.in/d/fA4iDgb Thank you for being a valuable subscriber to my newsletter Light Years! If you liked this post & found it informative, feel free to share this publication with your network by clicking the button below… I hope you found this post informative & it helped you in some way. As always, feel free to subscribe to my publication Light Years & support it & also share it if you’d like. Get it in your inbox by filling up the space below! You can find me on Medium on my Medium profile covering a plethora of topics (there’s a bit of difference between the posts here & there): https://medium.com/@gaurav_krishnan You're currently a free subscriber to Light Years by Gaurav Krishnan. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Friday, 6 February 2026

Why Mumbai Is Called The Maximum City

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Why Mumbai Is Called The Maximum City

A literary delve & summary of Suketu Mehta’s book Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏...

-

https://youtube.com/watch?v=IlPponrElbc&si=5ds0UtFazsvr-lFf ...

No comments:

Post a Comment