The Logic Brain, the Creative Brain & the Inner Censor — The Creative Process Explored FurtherOn Julia Cameron, mushin, the creative process, and why your best work begins when you understand these principlesCreativity has a certain flow to it. The flow state, also known in Japanese Zen philosophy as “mushin”, which roughly translates to “no mind”, is where the artist or warrior “flows” in a state in which action happens without interference. Initially mentioned in the Samurai code, “mushin” is where there’s no hesitation. There’s no commentary. Nor is there the self watching itself perform. The swordsman does not think about the strike; the strike just happens. Nor does the musician judge the phrase, but the phrase arrives fully formed. Mushin is clarity without obstruction & being in the state of complete immersion in the activity without thinking about the next move. Modern psychology would later call this flow. Artists recognise it instantly when it happens: it’s a rare window where time collapses, and self-consciousness dissolves, and the work seems to move through you rather than from you. However, this state is fragile. It disappears the moment the mind starts narrating itself. To better understand myself, my creative pursuits and creativity itself, I’ve been turning to many books, two of which I finished last year, namely, The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin & Steal Like an Artist by Austin Kleon. This year I’ve gone a bit further. In her book The Artist’s Way, which I’m currently reading, author Julia Cameron argues that “mushin” is difficult to sustain. However, Cameron frames the creative process & struggle as an internal tension between three primary forces: the Creative Brain, the Logic Brain, and the Brain Censor. Below, I’ll break down her analysis of each of these aspects & their pertinence to the creative process, along with her advice on how to deal with them. The Logic Brain: The AccountantThe Logic Brain is practical, structured, and linear. It’s the part of you that schedules studio time, edits drafts, balances budgets, and asks sensible questions like “Is this finished?” or “Does this make sense?” In her book & analysis, Cameron is careful not to villainise this part of the mind. The Logic Brain is essential, she adds. Without it, creative work remains amorphous, unfinished, or lost in abstraction. It is order, structure, and measurement. It wants clarity, outcomes, and guarantees. It asks sensible questions: Does this work? Is this useful? What are the processes needed? It is the part of us that edits drafts, arranges notes, meets deadlines, and knows when something is finished. Without the Logic Brain, creative work never enters the world. It stays private, incomplete, unrealised. Albums wouldn’t be mixed & mastered. Manuscripts wouldn’t be revised. Films wouldn’t be released & so on & so forth. It’s a mechanical process, which I like to think of as adding the processing to certain sections of my track in my DAW after I finish writing the ideas. However, Cameron argues that the Logic Brain tends to arrive too early. When it dominates the beginning of the process, instead of refining ideas, it vetoes them. It demands coherence before chaos has done its job. It wants proof before play. And in doing so, it confuses control with intelligence. The Logic Brain has a fatal flaw: it believes it should be in charge all the time. This is where it can stifle creativity & the work of the Creative Brain. Cameron’s advice suggests that logic belongs after creation, not during it. The Logic Brain shouldn’t be mistaken for leading the creative process; it’s a tool for after the creative process is finished, argues Cameron. Its role is to shape, edit, organise, and complete and not to decide whether an idea deserves to be born. When logic enters too early, it acts like a gatekeeper rather than a craftsman. Cameron encourages artists to consciously assign logic to a later role in the creative process. So she elucidates that now I create, later I refine, and it is one of her most practical solutions to the creative process, in its entirety. She restores logic to its rightful place without allowing it to dominate the boundlessness of the imagination. The Creative Brain: Where the Creative Work Actually Comes FromThe Creative Brain, on the other hand, is nonlinear, intuitive, playful, and irrational. It thinks in images, fragments, emotions, and half-formed ideas. It doesn’t explain itself. It doesn’t justify its impulses. It simply offers them. This is the part of the brain that says, “What if?” This is precisely where melody appears without instruction, where metaphors surface unannounced, and where sentences arrive already predestined. Cameron insists that creativity is not something we force but something we allow. The Creative Brain works best when it feels safe, i.e. safe to be messy, safe to be bad, safe to be unfinished, she adds. And this is precisely why it’s so vulnerable to attack. The Creative Brain doesn’t respond well to interrogation. It needs space, safety, and a suspension of judgment. Above all, it needs permission to be bad. Cameron’s advice is simple when it comes to the Creative Brain:

Cameron argues that ideas are received, whereas they only seem like a by-product of effort. The artist’s job, she says, is not to interrogate the impulse but to follow it. Doubt, analysis, and refinement are for later, and they need to be postponed. According to Cameron, the Creative Brain works best when it feels a sense of comfort. Going further, she suggests that this means freedom from premature judgment. She urges artists to let ideas arrive incomplete, contradictory, even embarrassing. Essentially, the first draft isn’t final or the most evocative. It is meant to exist first. The Brain Censor: The Saboteur Disguised as IntelligenceHovering over both the Creative & Logic Brain is the Brain Censor, which is the most misunderstood aspect of the creative process. It presents itself as realism, maturity, and even at times, wisdom. But if you’re aware of it, you’ll recognise it as fear disguised as discernment. The Censor speaks early and confidently, always being a constant inner critic: “This is mediocre.” The Brain Censor often masquerades as logic, but actually, it is fear donning the robes of reason. Fear of judgment. Fear of failure. Fear of being seen. Fear of perfection. Fear of something else being better. I’ve faced this quite a lot in my work, especially early on in my creative journey. Cameron’s key insight is this: the Brain Censor is loudest at the beginning, when work is most fragile. Instead of helping improve the idea, it urges you to stop before it even begins or materialises into something tangible. The tragedy is that many artists mistake this voice for truth, she alludes. Cameron’s advice on dealing with the Censor is an important tactic for any creative person:

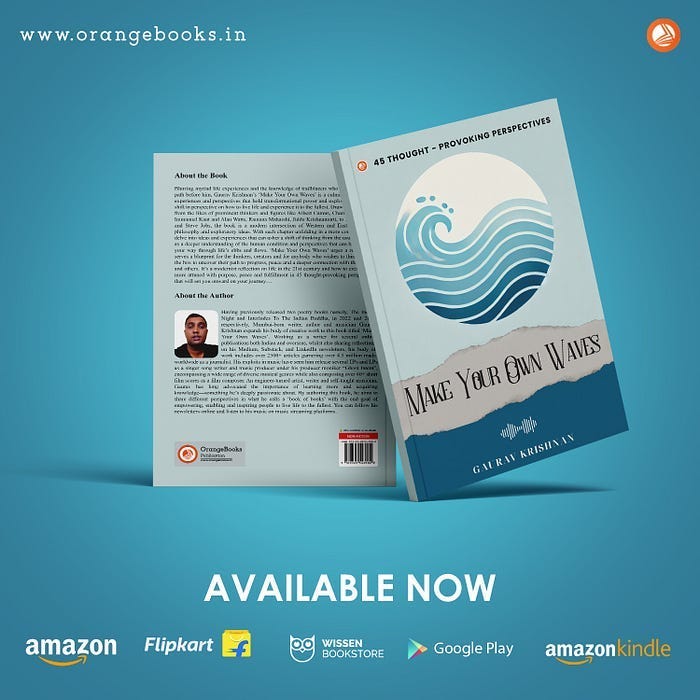

The Censor thrives on engagement with it. Cameron’s strategy to counteract this is by refusal. She says that it is perhaps imperative to ignore the Censor. By continuing to create in spite of the inner criticism, artists can gradually reduce its influence over their creative work. Over time, and with consistent practice, the Censor grows quieter. It, of course, doesn’t get eradicated entirely, but its influence on the artist wanes with time & conscious awareness of it. Importantly, Cameron reframes the Censor as fear rather than truth. Once this distinction is made, its authority collapses. The Core Tenets of Cameron’s AdviceJulia Cameron’s take on the creative process isn’t a system or a rigid framework. However, she does offer a psychological reordering of the creative process. Create first. We live in a society obsessed with outcomes, metrics, and validation, and so this may be her most radical instruction: let the work exist before you decide what it means. Creativity needs its space to breathe and come about. While I’m no expert, I have found this advice pretty useful in my creative process of making music & writing. Essentially, if you’re aware of the interactions of these core aspects of the creative process, it helps in making your creative work better. And while I don’t agree with some aspects of the book, it’s definitely a book worth reading, especially if you’re aiming to delve into your own creative work & creative process. If you liked this article, you can buy my book Make Your Own Waves, which comprises 45 thought-provoking perspectives on life, which you can buy at the link: https://amzn.eu/d/dZaX8Dr If you’re in India, you can buy it here: https://amzn.in/d/fA4iDgb Thank you for being a valuable subscriber to my newsletter Light Years! If you liked this post & found it informative, feel free to share this publication with your network by clicking the button below… I hope you found this post informative & it helped you in some way. As always, feel free to subscribe to my publication Light Years & support it & also share it if you’d like. Get it in your inbox by filling up the space below! You can find me on Medium on my Medium profile covering a plethora of topics (there’s a bit of difference between the posts here & there): https://medium.com/@gaurav_krishnan You're currently a free subscriber to Light Years by Gaurav Krishnan. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Sunday, 4 January 2026

The Logic Brain, the Creative Brain & the Inner Censor — The Creative Process Explored Further

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

-

https://youtube.com/watch?v=IlPponrElbc&si=5ds0UtFazsvr-lFf ...

No comments:

Post a Comment