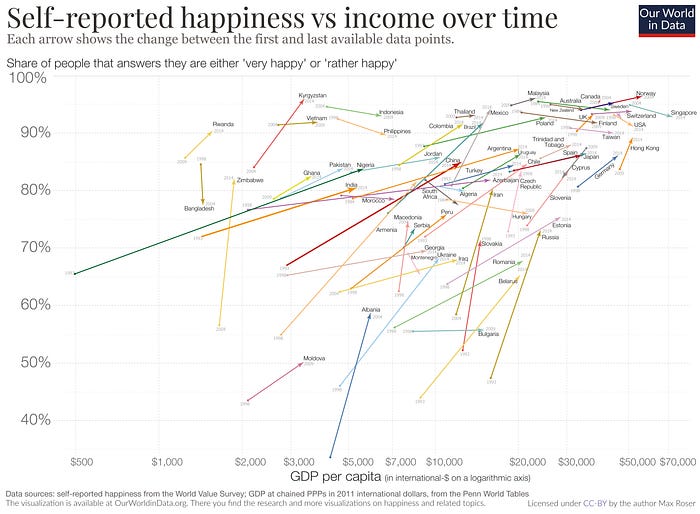

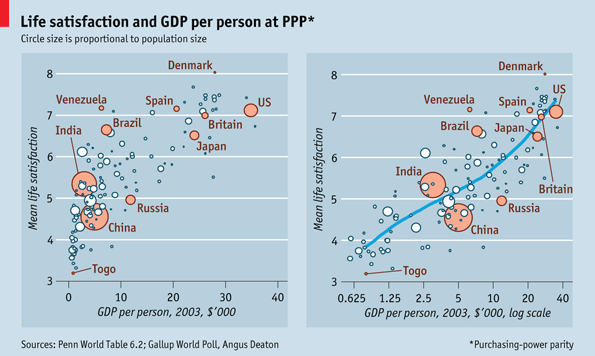

The Easterlin Paradox In Economics — Why GDP Growth Doesn’t Make Societies HappierAn essay examining the Easterlin Paradox and its implications for economic growth and societal well-beingIt’s past midnight in Mumbai city, the financial capital of India, and the city author Suketu Mehta dubbed the ‘Maximum City’ in his book Maximum City: Bombay Lost & Found, which I read several years ago. The air is a bit thick but chilly for the start of January 2026, & I’m halfway through writing an idea for a part of a short film score, but I didn’t want to overwork & rush myself on it. So I decided to write this short essay on the Easterlin Paradox, which was something I came across while doing my reading online recently & which I briefly studied & did a minor deep dive into. Here’s my brief essay on the subject, delving into the nuances and implications that emerge from the Easterlin Paradox. The Premise of the Easterlin ParadoxIn the mechanics of mainstream economics, when a country’s overall income rises, it should ideally translate to higher welfare. The Easterlin Paradox combines classical and behavioural economics to paint a clearer picture. Higher GDP per capita means greater consumption capacity and improved living standards, which should lead to greater happiness & societal well-being. However, the Easterlin Paradox exposes a structural anomaly in this assumption, challenging the narrative that linear growth in GDP leads to linear growth in happiness and well-being. First postulated by Richard Easterlin in the 1970s, the paradox observes that while within a country, at a given point in time, richer individuals tend to report higher subjective well-being, over the long run, as countries become wealthier, average happiness levels remain largely flat. This contradiction sits at the heart of modern happiness & welfare economics.

Absolute Income vs Relative IncomeThe crux of the Easterlin Paradox is based on the critical distinction between absolute income and relative income. Absolute income refers to material consumption and purchasing power. Relative income, on the other hand, is positional, i.e. it reflects one’s standing within a social and economic hierarchy. Human satisfaction, Easterlin argued, is fundamentally comparative, and not absolute. Individuals tend to almost always evaluate their well-being relative to peers, reference groups, and social benchmarks. And as incomes rise collectively (for the nation via economic output), relative positions remain unchanged. This results in a zero-sum happiness game, where aggregate growth fails to deliver aggregate psychological returns. This dynamic is further reinforced by status competition, in which income increasingly serves as a signal of social hierarchy rather than material well-being. In short, when the country, i.e. everyone upgrades, no one feels upgraded. Hedonic Adaptation and the Treadmill EffectAnother structural mechanism underpinning the paradox is hedonic adaptation. Hedonic adaptation is defined as the psychological process by which individuals rapidly adjust to improved circumstances. Income increases & raises, promotions, and consumption upgrades generate short-term spikes in happiness, but these gains wither & decay as new baselines are established. This produces what behavioural economists call the hedonic treadmill. Essentially, it suggests that individuals must continuously run (earn more, consume more, achieve more) merely to stay in the same subjective position. It’s like running on an endless treadmill where perceived growth becomes a maintenance activity rather than an actual transformative one. From a macro perspective, societies scale the treadmill collectively, which we often see reflected in higher productivity, longer working hours, and intensified competition(the latter especially for jobs & it’s something we’re seeing now with AI automation as well). However, this tends to occur without corresponding improvements in well-being. The Policy Failure of the GDP ModelThe Easterlin Paradox poses a direct challenge to the GDP-centric policy framework model. If long-term economic growth does not systematically raise happiness, then growth, as an end result, becomes analytically indefensible. Evidence from studies suggests that once basic needs are met, i.e. nutrition, healthcare, education, physical security, etc. marginal utility of income declines sharply. Beyond this threshold, factors such as job security, social trust, autonomy, leisure, and mental health become far more predictive of well-being than income growth. However, policy regimes continue to prioritise domestic output expansion, productivity metrics, and consumption incentives, which come at the expense of social capital and overall well-being.

Inequality Makes the Paradox WorseRising inequality further fuels the intensity of the paradox. As wealth concentrates at the top, baseline points shift upward. Aspirations for people rise faster than incomes, creating a permanent expectation gap where people feel poorer even while living materially better lives than previous generations. In such systems, money loses its ability to generate collective well-being despite increased economic output. Rethinking ProsperityThe enduring relevance of the Easterlin Paradox lies in the systemic implication that economic growth is a poor barometer for human flourishing once basic needs are met. It fundamentally suggests that societies cannot out-earn their psychological constraints. A post-Easterlin idea of prosperity means critically valuing: a) distribution over accumulation Without this conceptual change in policy, growth may look impressive in terms of data, but almost certainly will fail to improve & impact real lives. In the end, the Easterlin Paradox exposes a deep flaw in modern economics, in that we’ve built systems optimised relentlessly for growth in numbers and data, while quietly forgetting what growth actually is, and who it was meant to serve. If you liked this article, you can buy my book Make Your Own Waves, which comprises 45 thought-provoking perspectives on life, which you can buy at the link: https://amzn.eu/d/dZaX8Dr If you’re in India, you can buy it here: https://amzn.in/d/fA4iDgb Thank you for being a valuable subscriber to my newsletter Light Years! If you liked this post & found it informative, feel free to share this publication with your network by clicking the button below… I hope you found this post informative & it helped you in some way. As always, feel free to subscribe to my publication Light Years & support it & also share it if you’d like. Get it in your inbox by filling up the space below! You can find me on Medium on my Medium profile covering a plethora of topics (there’s a bit of difference between the posts here & there): https://medium.com/@gaurav_krishnan You're currently a free subscriber to Light Years by Gaurav Krishnan. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Friday, 9 January 2026

The Easterlin Paradox In Economics — Why GDP Growth Doesn’t Make Societies Happier

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

-

https://youtube.com/watch?v=IlPponrElbc&si=5ds0UtFazsvr-lFf ...

No comments:

Post a Comment