"Thanks for getting me out here, babe." My voice is excited but gruff. "I didn't get much sleep at all last night."

I'm feeling the effects of our 2021 all-day New Year's celebration. Despite some muscle aches, moderate anxiety, and a tad bit of brain fog, I'm happy to be out in the mountains with my wife. We've been hiking trails in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park together for years. Now Katie wants to start our first official "trail map." Today's groundbreaking hike starts under a cerulean blue sky that shines white and gold light across the mountaintops – a perfect way to start our goal to hike all 900 miles worth of trails in our favorite national park.

With the hike planned well in advance, we dropped Eli off at my mom's house early on New Year's Day. Back at our place, amid the cooking of Hoppin' John (a bacon and ham laden black-eyed peas and rice dish) stewed greens, and cornbread, we consumed plenty of champagne together, and I also purchased some brandy. My wife and I listened to music and hung out on the back deck to simply talk, dance, and celebrate our new home. The sunny afternoon gave way to a pale evening, then evening gave itself to night's darkness. Katie was smart and retired at a reasonable time. However, my late-night genes kicked in. So, the music rang loud, the brandy splashed the rocks, and I was up all hours of the night. This morning I am running on roughly two hours of distilled sleep.

"Of course, my love," Katie responds with a soft voice. "You were rather wild last night. How are you today? We have about twelve miles ahead of us."

"I'll be good! I feel surprisingly well, all things considered," I answer, scratching my beard. "Feels great this morning, and that hot sandwich and coffee really hit the spot."

"Well good! I think this is going to be fun. I don't think I've ever been on Finley Cane or Crib Gap."

"I know I've not, though I've eyeballed this loop and Turkey Pen numerous times. We've hiked the same loops for years now. Hell, I've been coming to this park since I was in high school. I drove right by this trail a million times thinking it'd be cool to do but have never done it."

This past Boxing Day, I pulled my old copy of Elizabeth Etnier's Day Hiker's Guide To All The Trails In The Smoky Mountains out of a box in my office. Katie and I figured we'd just hike all the trails in the author's order. Etnier's book is a comprehensive review of all the trails in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. She's hiked them all herself, and her book provides maps, logistics, simple directions, and helpful information. Our first trail is an 11.8-mile loop along Finley Cane, up and down Bote Mountain, across Crib Gap, and out Anthony Creek. Our hike will prove steep, rocky, eroded, muddy, bright, beautiful, and rewarding.

We begin our walk along Finley Cane Trail shortly after nine o'clock in the morning. The air is crisp but not cold. The sun shines bright in a crystal-clear blue sky. Between the tree limbs and the forest floor's brown leaves, the Earth around us rolls and glows in mountain wonder. Winter in the park is a very special time. Leaves are in decay on the trail, save those rattling in the breeze on birch branches, or drooping on rhododendron. The Appalachian Forest slumbers but the land folds and flows.

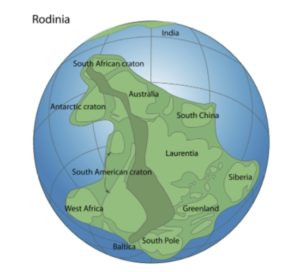

These Appalachian Mountains hold rock units that are over one-billion-years-old. These slabs of ancient rock likely cooled at different times over a 150-million-year period after large chunks of continental crust collided in what geologists call the Grenville Orogeny((Orogenies are mountain building events.)) some 1.2 billion to 980 million years ago. This mountain building event occurred as a supercontinent, known as Rodinia, emerged from tectonic forces. At this time, these sleepy Appalachian Mountains likely resembled the modern mountains of Tibet – steep in form and ascending towards the heavens.

Over the next 250 million years, Rodinia's mountains weathered and eroded, punished by storms, freeze-thaw, and gravity's relentless pull. Boulders crumbled to stone, stone cracked to cobble, cobble rounded to sand, silt, and clay. Roughly 750 million years ago, Rodinia began to rift apart. This rifting caused Earth's crust to crack, like the outer shell of a hard-boiled egg. From the depths of the rift valleys, molten rock spewed to the Earth's surface as fiery lava.

As the years passed, Earth's crust continually thinned and stretched. Plate tectonics delivered more crustal uplift and subduction. Basins, circumscribed rock formations where strata dip toward a universal center, formed as Rodinia pulled apart. One such basin was home to the Iapetus Sea. Like today, deep in the geologic past, rivers constantly cut into surfaces eroding hard rock and carrying their sand and mud to the basin valleys. These sediments would be subject to tectonic forces – heated and pressed into metamorphic rocks.

When Rodinia fully rifted apart, our neck of the woods was on the edge of a supercontinent known as Laurentia. On the horizon was the new, expanding Iapetus. Continental crust continued to thin and crack, magma continually busted through the surface in fiery explosions across the land. Volcanoes rose from violent forces within the Earth, spewing glassy lava and welded tuffs across the landscape. Plate tectonics, in constant movement, buried these igneous rock structures deep. These structures thrust laterally and vertically. Slabs of Earth compressed the lithology, causing new metamorphism that produced minerals of plagioclase, pyroxene, olivine, and epidote.

Another 200-million-years passed until Laurentia collided with Gondwana – modern day Africa. This collision, known as the Alleghenian or Appalachian Orogeny, was so powerful that Laurentia buckled and cracked. Huge continental blocks of rock were thrust on top of Grenville-age strata. All the mountains were folded and squeezed in high temperature and pressure. The Appalachians rose even higher, standing as 30,000-foot titans across the vast supercontinent of Pangea.

In Greek mythology, Iapetus was the father of Atlantis. Therefore, the Iapetus would vanish so the Atlantic could follow. The Iapetus Sea crashed waves across an expansive, unifying landmass, only to be lost forever to geologic time as Pangea fully came together. At the end of the Appalachian Orogeny, approximately 200 million years ago, when the Paleozoic era was ending, the mountains stood 22,000 feet in the air and resembled the modern-day Andes.

Pangea began a long breakup when the Mesozoic era started. The great rift took place about 220 to 180 million years ago. This tectonic motion split Pangea into today's continents. Further, as dinosaurs roamed the Earth, the land masses began a long journey to their modern-day locations. At the time, magma welled up from the bowels of our planet to push the continents away from each other. The cooling magma oozed from cracks in the Earth's crust and formed the basalt-laden floor of the Atlantic Ocean.((Basalt is rock formed when lava cools after reaching Earth's surface.)) To this day, the Atlantic Ocean expands a few centimeters every year as North America migrates closer to China.

Of course, the Appalachian Mountains have done nothing but weather and erode since Pangea rifted apart. I love to contemplate the deep history here – from titans like the Himalayas, to sentinels like the Andes, to the wisdom of a folded terrain that Katie and I walk across today. Yes, with the leaves gone, an unobstructed view of the land steals the show.

As Katie and I stroll along the Finley Cane trail, we wind up and down a nice pathway covered in musty leaves. Several stream crossings present us no real difficulty. Their waters reflect the sun and shine bright in the morning glow. We walk among healthy stands of American Holly and a uniquely tall woody grass in the last mile or so of the trail before reaching the junction with Bote Mountain.

Image of Arundinaria gigantea by James H. Miller and Ted Bodner on Forestry Images

The woody grass is a river cane, though most folks would simply call the plant bamboo. River cane, though, has but one species native to North America, Arundinaria gigantea. At one moment in time, this species was rather abundant across North America. River cane occupied millions of acres of floodplains, coastal prairies, savannahs, and wet mountain biomes across the Southeastern United States until European settlement came to the area. Throughout the 1700s, river cane was cleared for agricultural fields and later urbanization. As a result, healthy populations of the wooded grass, known as canebrakes, are almost non-existent today. In fact, canebrakes are so rare they are considered critically endangered ecosystems.

The loss of canebrakes throughout the Southeast has caused a myriad of environmental problems. The grass is a great soil stabilizer. Without the native plant, soil erosion and flash flooding has become a major environmental issue across the South – together with clear-cutting forest ecosystems. Further, river cane grows in dense thickets and may reach a height of twenty feet tall. The woody stem itself is usually an inch in width at greatest, but the leaves that diverge can measure fifteen inches in length, and two inches wide. This habitat is especially great for migratory birds. Many ornithologists (scientists who study birds) believe the loss of canebrakes has led to the extinction of Bachman's warbler. Other warbler species in critical endangerment are also missing the vital habitat space. Beyond songbirds, butterflies and numerous endemic plants are also at risk to extinction due to the loss of the native woody grass.

1907 Image of Bachman's Warbler, male (L) and female (R) by Louis Agassiz Fuertes - Wikimedia

What we are learning, as our sixth mass extinction progresses, is that, when one species is lost, a cascading effect of endangerment and extinction can be expected. In the conservation sciences, this phenomenon is often referred to as the "rivet-hypothesis." A good way to demonstrate what this means is to imagine flying on a plane. We're a lucky passenger with a window seat to enjoy the view as we soar through the sky. Between sips of ginger-ale, we peer out the window and notice one of the metal pins on the wing is wiggling. The vibration becomes so intense, the rivet pops out of socket. Troubling, but all is still well, we think. Surely one screw cannot do much – but, as it turns out, an aluminum panel on the wing pops off minutes later. The plane itself is still intact, but now all the passengers are experiencing a great deal of turbulence. As the cabin shakes, and pressure mounts on the remaining panels, another rivet is lost – now we find ourselves in dire straits. If the wing of the plane is lost, we all go down. In this way, we understand the rivet hypothesis: If certain biomes lose an important species, several species will surely be lost eventually. This continual loss can lead to a total collapse of ecosystem function. Although the decrease in ecosystem function may be slow, the rate of failure increases as more species are eliminated.

Ever since the origin of our species, humans have interacted with the natural environment. In all this natural history, I find it amazing that forces of deep time shape and mold our very human animal to this day. Our current relationship with the environment is the product of our collective history. Although we may not have intended to bring about global environmental changes, humankind clearly and unquestionably has had a global impact on natural systems.

Image of deforestation (R) by Justus Menke on Unsplash

There was, and in many ways still is, an idea in human societies that we, as a species, could separate ourselves from the living world around us. We are to rule over and have "dominion over the Earth." A desire to tame wildness exists in our species. Nature is displayed as a violent place of unforgiving competition. However, even as the natural world is often violent, it is also a place of complex mutualism, co-evolutionary/symbiotic relationships, resiliency, rhapsody, and more. In our quest for dominance, the violence of our human technologies, specifically the use of fossil fuels to advance our civilization, inflicts incredible, exponential damage to our planetary system.

Our species has built systems of power and domination. Trouble is, fossil fuel technology has not just changed human civilization, but the disruption of natural cycles has very literally changed the planet we inhabit. Further, human well-being, our economic lives, have wrought a lifestyle of never-ending production and consumption. This system fuels deforestation, mining, ocean resource depletion, industrialized agriculture, and more.

More and more people are realizing we live on a finite planet, with finite resources, and the clock is ticking to clean up the mess we have made. Further, we are discovering that a sustainable life does not mean we have to give up our comforts, but instead expand them in new ways. I find a lot of hope in this realization, especially for our younger generations.

Visit the site Thursday for part two of Grant Mincy's "Earthlings"!

**Featured image by Septimiu Balica on Pixabay